Surgery is a fact that has emerged with humanity. In primitive ages, surgery was not a separate specialty. In these times, people performed surgical procedures to heal wounds and stop bleeding or cut the limbs that have lost function. In this article, we’ll try to explain to you The Origin of Surgical Saw Blades and Blade Types”.

Blade-like objects that people initially made to protect themselves or to feed themselves became the main building block of surgical procedures.

Researches in the last century has shown that human nails are used like primitive surgical blades, scalpels or curettes. Engelmann (1886) recorded that the Klatsoops tribe in North America cut the umbilical cord with their nails after birth. While being examined traditional Ethiopian surgery, Pankhurst (1964) stated that infected tonsils were burst or were completely cut off with the help of a long nail (Kirkup, 1995).

No positive evidence can prove that the nails directly affect the invention of the blades, but it is interesting that some surgeons recommended nail-like products in metallic form in the late 19th century for nasal operations (Figure 1)(Kirkup, 1995).

Figure 1 – Nickle-plated steel ‘thimble’, late nineteenth century, (Kirkup, 1995)

Sharp leaf edges, stems of some palm, reeds, bamboo and rigid herbs can be razor-like. Therefore it is not surprising that they are used as surgical blades. Engelman (1886) reported that the Loanga Tribe in Africa cut a umbilicus (belly) with a sharp palm leaf stem and a piece of bamboo (Kirkup, 1995).

Lillico (1940) stated that some tribes in Melanesia and Polynesia performed scarification (incisions in the body) with bamboo stems and thorns (Kirkup, 1995).

Comey (1925) witnessed external urethrotomy with mussel shells and broken mussels in Fiji.

Ellice islanders have performed scarsification with shark teeth mounted on some stems. Karaya Indians of Brazil performed scarification with a series of river fish teeth fixed with wax to a quadrangular or triangular piece of shell (Kirkup, 1995).

In the late 19th century, in Europe, it is seen that thin ivory blades were sold, each sold in packs of 100 for a single application, forming the earliest form of a disposable surgical blade (Figure 2) (Kirkup, 1995)

Figure 2 – Single use ivory blades, late nineteenth century (Kirkup, 1995)

More productive lancets and scalpels were made of flint, obsidian (volcanic glass) and other siliceous rocks, in beginning as accidents of nature, split by heat, frost, glaciation, earthquake, sea action and by man’s haphazard breakage (Kirkup, 1995).

Naturally broken stones were probably used as the first hand tools. Even today, there are tribes that use sharp stones, shark teeth, and mussel shells as tools (Oakley, 1961).

In the paleolithic period (before 8000 BC) and especially in the Neolithic (8000 to 3000 BC), manual skills were developed to create various surgical blades, but they are impossible to be specific to surgical procedures (Kirkup, 1995).

Lillico (1940) stated that the primitive blood-letting by scarification was made by American Cherokee and Alaskan Indians with flint flakes and Bering Strait Eskimos with nephritis (jade). American Chippewa and Mapuche Indians performed blood-letting with nailed flint lancets to the stems or with arrowheads (Kirkup, 1995).

In recent years, Crabtree in the USA has revived the old method of producing thin blades made of volcanic glass and they convinced his surgeon ’Buck’ to use it for half the incision in the operation. Buck reported that volcanic glass is sharper than stainless steel and following recovery is normal. (Jacobs, 1939).

Later, Buck recommended these blades for nerve repair, microvascular, plastic, and ophthalmological surgery. Unfortunately, time-consuming production skills have not been able to compete economically with mass-produced disposable steel blades. (Kirkup, 1995)

The melting of iron around 1400 BC and the discovery of the ‘steel’ face of iron pieces around 1200 BC were other revolutions that improved the quality of weapons and tools (Forbes, 1954). Before Hippocrates mentions iron blades for scarification (before 400 BC), any documented practice for surgery is unknown. (Adams, 1849).

Along with the crucible (casting) steel process; The production of sharper, stronger and corrosion-resistant blades took place in the middle of the eighteenth century (Forbes, 1956).

These blades, which are aligned at right angles or obliquely to the long axis of the tool, operate with strong pushing or hammering motion, mainly when cutting bone, cartilage or fibrocartilage (Figure 3)(Kirkup, 1995).

These blades, derived from the tools of the carpenters, were used to legally cut hands and feet long before the surgical amputations. According to the laws of Hammurabi, in 1750 BC, medical doctors whose treatment resulted in the death of their patients were punished with a hand amputation (Sigerist, 1951).

Until anesthesia was found, doctors and scientists worked on the blades to reduce pain in the amputation process and to shorten recovery period (Kirkup, 1995)

In 1879, Macewen introduced the equal-angle “chisel” (Figure 3, first picture) for accurate and controlled osteotomy of the lower femur (Macewen, 1879). This wedge-shaped end blade still holds a place in orthopedic practice, although power tools are used (Kirkup, 1995)

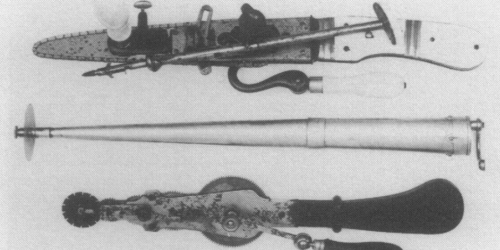

Figure 3 - End-blades from top to bottom; (Kirkup, 1995) - Steel osteotome, late nineteenth century, Macewen's equal-angled ‘chisel' for lower femur; - Steel meniscotome, mid twentieth century, Smillie's for knee; - Steel and ebony tonsillotome, early nineteenth century, probably Bell's; - Steel and aluminium tendon stripper, mid twentieth century, Bunnel's; - Steel and ebony gorget, early nineteenth century, Cooper's for perineal lithotomy; - Steel mastoid chisel, late nineteenth century.

Examples of saws used for bone shaping and amputation in the 19th century are given in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4 – Linear and Cylindrical Saws (Kirkup, 1995)

– Narrow steel blade and ebony, mid nineteenth century, Adams for osteotomy femoral neck;

– Steel skull trephine, dismounting from bone handle, early nineteenth century.

Figure 5 – Linear Saws (Kirkup, 1995)

– Steel serrated blade, detachable, for bow saw, early ninteenth century;

– Steel and composition tenon saw, reinforced back, selfclearing teeth, early nineteenth century, Weiss’s.

In the early 19th century, Larrey introduced a narrow linear saw for small amputations and joint resection. In 1869 Adams introduced a narrow saw with a pistol handle for subcutaneous osteotomy of the femoral neck relevant with joint stiffness (Figure 3, First Picture) ( Willet, 1898).

Click here to read more articles about surgical saw blades via PubMed website.

In the 19th century, some inventions emerged for easier cutting in bone shaping and amputation. (Figure 6) However, these inventions were costly, heavy and difficult to use devices. At the same time, they could not provide sufficient speed.

In 1908, Bryant released a lightweight, hand-held, electrical, with a speed 15.000 rpm power tool for cranial surgery (Figure 7)

With the help of high speed, together with power tools, incisions were started to be performed that cause less damage to the bone.

In time, the circular saws have been replaced by oscillating saws used together with the cutting guides.

The development of electrical and pneumatic systems has progressed together. Electrical systems are still used today. However, the use of pneumatic systems has decreased. The reason for this that it is difficult to use and prepare.

Today, battery powered power tools systems are preferred in terms of easy use.time, they could not provide sufficient speed.

Figure 7 - Electrical Saw (Bryant, 1908)

Figure 1 – Nickle-plated steel ‘thimble’, late nineteenth century, (Kirkup, 1995)

Figure 2 – Single use ivory blades, late nineteenth century (Kirkup, 1995)

Figure 3 – End-blades from top to bottom; (Kirkup, 1995)

Figure 4 – Linear and Cylindrical Saws (Kirkup, 1995)

Figure 5 – Linear Saws (Kirkup, 1995)

Figure 6 – Hand-powered saws, from below; (Kirkup, 1995)

Figure 7 – Electrical Saw (Bryant, 1908)